CASE OF THE WEEK – “Precise localization of biliary leak post laparoscopic cholecystectomy with hepatobiliary scintigraphy & adjunct hybrid SPECT-CT imaging” by Dr ShekharShikare, HOD & Consultant, Nuclear Medicine NMC Royal Hospital Sharjah

Introduction

Postsurgical bile leaks can be associated with significant morbidity and even mortality, if not identified and treated at an early phase. Hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HBS) scan is an important test for the detection of bile leaks in the postoperative abdomen. However, the lack of anatomical details on planar images can make interpretation difficult, especially in the setting of altered postsurgical anatomy. Familiarity with the expected postoperative appearance on HBS scan and correlation with single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) or other imaging modalities when available are very important.

A 37-year-old female underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis with cholecystitis and had uneventful recovery. The drainage tube kept postoperatively was removed next day before the discharge.

The patient was readmitted on the 3rd day with complaining of abdominal pain; her white blood cell was 19, C-reactive protein 39.2, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 63, serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase 90, and direct bilirubin 10.2.

CT scan of the abdomen with contrast was performed and showed free fluid within the peritoneal cavity, more prominent in the dependent portion of the abdomen (pelvic cavity). The operated cholecystectomy site appeared normal with surgical clip in situ. No intra- or extrahepatic biliary dilatation was seen. The above findings were similar to those seen in the previous magnetic resonance imaging examination. Ultrasound of the abdomen

Mild free fluid was seen, right adnexal, paracolic, and hepatic regions.

99m Tc-mebrofenin hepatobiliary scan

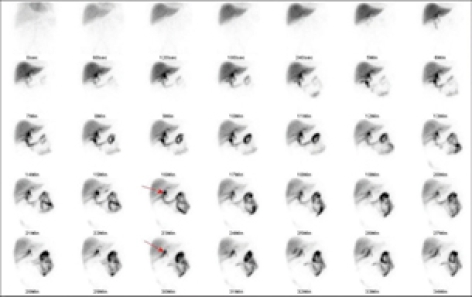

After intravenous administration of99m Tc-mebrofenin, sequential a) dynamic abdominal images were obtained over 60 min b) static images were obtained at 60 min & 120 min and SPEC T-CT FUSED images at 60 minutes. It shows good hepatocytic function by the liver and non-obstructive biliary to bowel tracer transit.

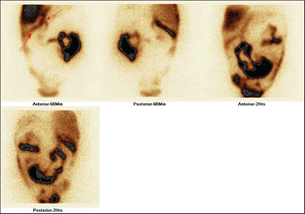

Abnormal tracer leak started seeing approximately from the confluence of cystic and common hepatic duct region [Figure 1] and [Figure 2] arrows, moving to the gall bladder fossa and then moving downwards from the inferior border of the liver [Figure 2] arrow and accumulating in peri-hepatic, infra diaphragmatic, right para-colic, left para colic region and eventually throughout the abdomen [Figure 2].

After intravenous administration of99m Tc-mebrofenin, sequential a) dynamic abdominal images were obtained over 60 min b) static images were obtained at 60 min & 120 min and SPEC T-CT FUSED images at 60 minutes. It shows good hepatocytic function by the liver and non-obstructive biliary to bowel tracer transit.

Abnormal tracer leak started seeing approximately from the confluence of cystic and common hepatic duct region [Figure 1] and [Figure 2] arrows, moving to the gall bladder fossa and then moving downwards from the inferior border of the liver [Figure 2] arrow and accumulating in peri-hepatic, infra diaphragmatic, right para-colic, left para colic region and eventually throughout the abdomen [Figure 2].

Figure 1: Hepatobiliary scintigraphy dynamic images showing active biliary leak (arrows)

Figure 2: Hepatobiliary scintigraphy static 60 min and 2 h images showing site of the lean (single arrow) and then through the inferior border of the liver (two arrows)

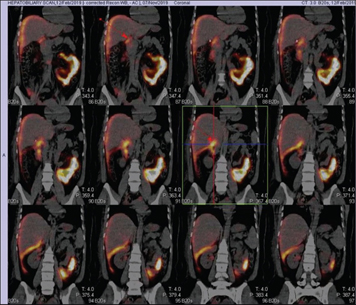

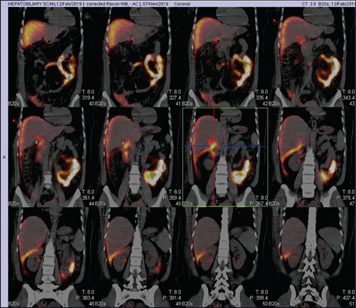

Adjunct SPECT/CT was performed at sixty minutes selectively for precise Anatomical localization and it showed active site of the biliary leak approximately at the confluence of cystic and common hepatic duct region [Figure 3] and [Figure 4] arrows.

Figure 3: Hepatobiliary scintigraphy single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography fusion images showing site of the biliary leak (arrows)

Figure 4: Hepatobiliary scintigraphy single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography fusion images showing site of the biliary leak (arrows)

Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed post HBS and 2 mm biliary leak point was identified approximately at confluence of cystic duct and common hepatic duct region, which is most probably due to burn injury. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed with stenting of the common bile duct and the patient settled and the stent was removed after 6 weeks.

Discussion

Bile leaks can occur after laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the incidence of injuries to the Common bile duct was 0.1%–0.6%. Imaging modalities used to detect bile leaks are CT, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), ultrasound, and HBS. Among these, only HBS and MRCP, noninvasive studies, can identify abnormal fluid collection as bile. However, there are limitations to emergency MRCP, including lack of readily available MR imaging equipment, technologists, personnel experienced with interpreting MRCP, and higher cost. Therefore, HBS is the commonly used modality to diagnose biliary injury.

HBS is a highly sensitive imaging modality and useful for early diagnosis of bile leaks. HBS can determine whether a fluid collection seen on ultrasound or CT is of biliary origin. HBS can determine the rate of leakage and can be used as a follow up tool A common finding of a bile leak is the radiopharmaceutical's progressive accumulation outside the biliary system, either localized (bilomas) or diffuse.accurate localization of a bile leak is possible by HBS along with adjunct use of SPECT/CT imaging to get anatomical information. This localization is important because of the shift in management strategy from very invasive to minimally invasive. This case demonstrates a direct bile leakage sign. this direct sign leads to recognition of an exact bile-leaking site at the confluence of cystic and common hepatic duct region. Determination of type of injury based on Nagana classification is useful in deciding the optimal management and the likelihood of success with conservative measures While most intrahepatic bile duct leaks (Nagano Type A) are self-limiting and respond to external drainage, some major leaks (Nagano Types B and C) often require ERCP and stent placement in the common bile duct and a select few patients with Nagano Type D injury require surgical management in the form of biocentric anastomoses or liver resection. Accurate localization of the site of bile leak through a direct sign can be obtained with HBS and HBS SPECT/CT as shown in this case. The HBS SPECT/CT provides both anatomic and functional information and overcomes the lack of specificity of CT alone or detailed anatomic information of HBS alone.

Conclusion

The precise site of a bile leak is possible with HBS noninvasive techniques as demonstrated in this case. Knowledge of the bile leak site will increase opportunities to detect the direct sign of a bile leak in advanced HBS with SPECT/CT. This has given the change in approach regarding management of a bile leak from less invasive to more invasive.

Ref –Shikare SV, El Hakeem A. Precise localization of biliary leak post laparoscopic cholecystectomy with hepatobiliary scintigraphy & adjunct single photon emission tomography? Computed tomography fusion imaging. World J. Nucl Med. volume 19/ issue 3/ July-sept180-3